What Makes Green Peppers Turn Red?

If you’ve ever wondered whether you can ripen bell peppers indoors to enjoy those sweet, vibrant red peppers even after picking them early, you’re not alone. It’s fascinating to watch green peppers gradually shift to rich shades of red, yellow, or orange—a process that signals not just a change in color, but a transformation in flavor and nutrition.

Peppers naturally start off green due to chlorophyll, the pigment that helps them convert sunlight into energy. As they mature, biological triggers kick in: ethylene gas, which plays a major role in fruit ripening, begins to build up. This hormone triggers the breakdown of chlorophyll and the production of carotenoids—the pigments responsible for the red, orange, or yellow hues.

Unlike tomatoes, which are classified as climacteric fruit and can fully ripen off the plant with the help of ethylene, bell peppers are considered non-climacteric. This means their ability to ripen after being picked is limited, but with patience, warmth, and a little help from being placed in a paper bag or on a sunny windowsill, you can encourage some further ripening at home.

The color change in peppers is more gradual and less predictable than in tomatoes; while tomatoes continue to soften and sweeten rapidly post-harvest, bell peppers ripen more slowly and may not always reach full redness indoors. Still, ripening bell peppers indoors offers a smart way to avoid pests or bad weather and get the most from your garden harvest—even if your peppers need a little extra time to reach their peak color and flavor.

The Science Behind Peppers’ Color Change

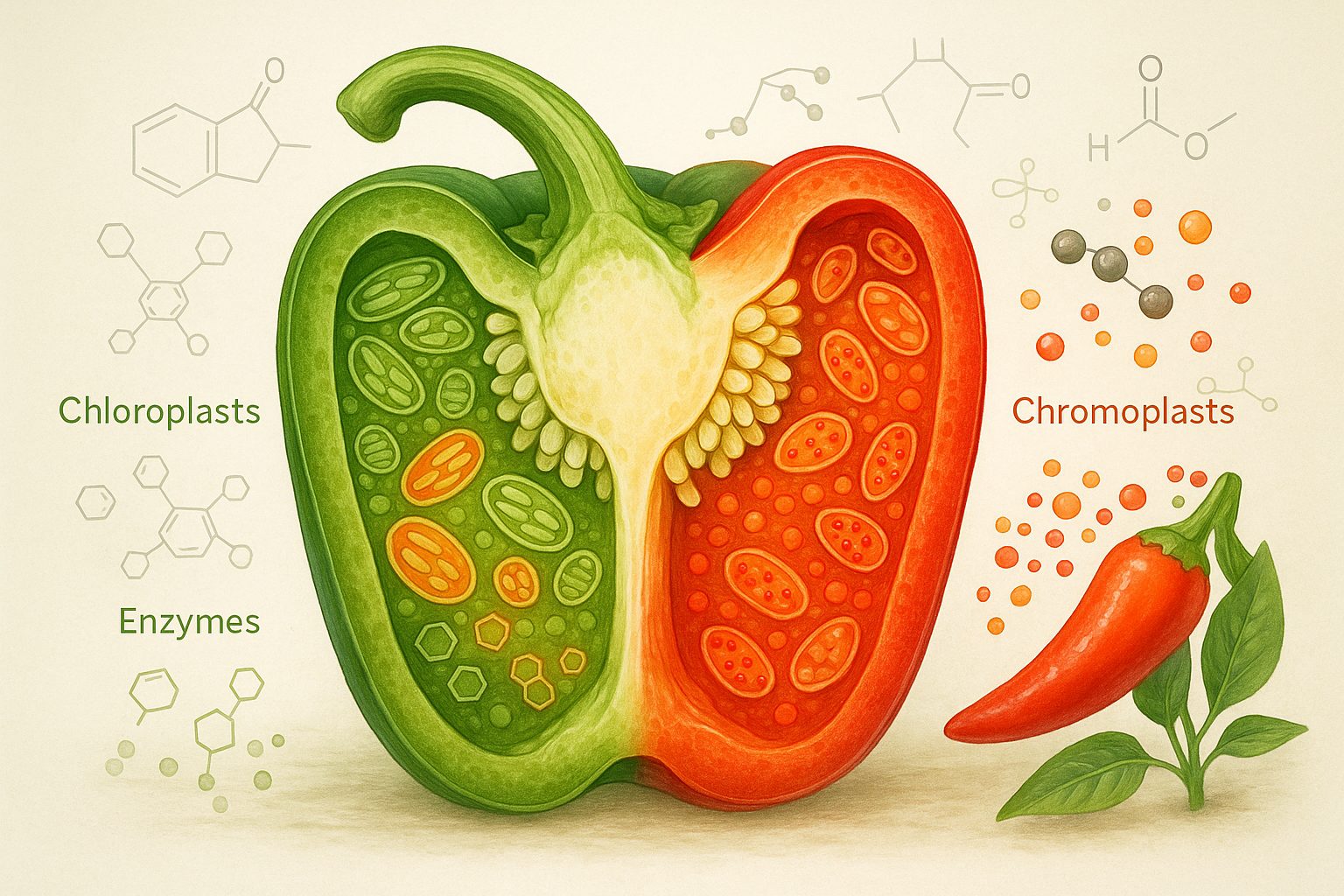

As peppers ripen, their transformation from green to vibrant red, yellow, or orange is a fascinating display of plant science in action. Early in development, green peppers are rich in chlorophyll, the pigment responsible for photosynthesis. As the fruit matures, specialized enzymes begin breaking down chlorophyll while simultaneously ramping up the production of carotenoids—pigments that create the rich colors associated with ripe peppers.

At the protein level, enzymes like chlorophyllase and peroxidase become more active, accelerating the degradation of the green pigment and enabling the accumulation of carotenoids such as beta-carotene and capsanthin. On the cellular front, plastids within the pepper cells, originally functioning as chloroplasts, are remodeled into chromoplasts—a transformation unique to peppers and a few other fruits like tomatoes.

Unlike many fruits where color change can happen post-harvest due to ethylene gas, most pepper varieties need to fully mature and remain on the plant for carotenoid development and full color intensity. This scientific sequence not only marks visual ripeness but also mirrors flavor evolution: as chlorophyll fades and carotenoids increase, sugars accumulate and bitterness decreases, resulting in sweeter, more complex-tasting peppers.

So, when shopping or harvesting, the shift from green to a bold, mature hue provides a reliable sign of optimal flavor, nutritional value, and culinary versatility—a direct benefit of the intricate cellular and molecular changes peppers undergo as they ripen.

Environmental and Growing Conditions Affecting Ripening

Climate plays a crucial role in how and when peppers ripen, especially in the transition from green to their final mature red color. Warm temperatures between 70°F and 85°F during the day are ideal, giving pepper plants the steady heat they need for sugars to develop and colors to fully shift. Cooler nights are fine, but consistent drops below 55°F can stall ripening or cause uneven color.

Late-season frosts are particularly harmful, sometimes halting the ripening process altogether or leaving you with peppers that never turn red. To protect plants as the weather cools, use row covers or bring potted peppers indoors overnight. For gardeners in short-season climates, choose early-maturing pepper varieties or start seeds indoors to maximize the growing window.

Peppers also need ample sunlight—at least six hours daily—and well-drained soil rich in organic matter to support even growth and vibrant color. On the flip side, harvesting too early or facing long stretches of overcast, wet, or excessively hot weather can stunt ripening or result in pale, less flavorful peppers.

While it’s tempting to pick peppers for green consumption, remember that those left on the plant longer (under the right conditions) will develop the sweetest taste and deepest hue. In cases of early frost warnings or persistent cold, you can pull whole pepper plants and hang them indoors to allow fruits to finish ripening off the vine, though results may not match the quality of sun-ripened produce.

Monitoring the forecast, adjusting your watering, and providing shelter during cold snaps are simple, practical ways to support your peppers through their final color change and enjoy a bountiful harvest.

Harvesting and Storing Peppers for Maximum Flavor and Nutrition

For the richest flavor and highest nutrition, it’s best to harvest peppers only after they’ve fully ripened to their final color—usually a deep, vibrant red for many varieties. Peppers ripening on the plant absorb more sunlight and nutrients, becoming sweeter and more nutrient-dense than those picked early.

However, if cooler weather threatens or frost looms, you can pick peppers when they begin to show their mature color and finish ripening them indoors. Simply place them in a single layer on a windowsill, countertop, or in a shallow box on newspaper, ideally in a warm area with indirect sunlight. To speed things up, put a ripe banana or apple nearby—the ethylene gas they emit can trigger peppers to ripen more quickly.

Once your peppers reach peak ripeness, store them unwashed in the refrigerator’s crisper drawer in a breathable produce bag or paper bag; this helps them stay crisp and prevents mold.

Alternatively, if you have a bounty, consider freezing sliced peppers, sun-drying, or dehydrating them for longer storage—these methods preserve most of the flavor and nutrients. Always avoid storing peppers in airtight containers without drying, as trapped moisture can quickly lead to spoilage.

By following these harvesting and storage tips, you can enjoy the true taste and health benefits of homegrown peppers long after the harvest season ends.

Why Some Peppers Stay Green – Varieties and Common Questions

If you’ve ever waited for a green pepper to turn red—only to find it never does—you’re not alone. Some pepper varieties, like certain jalapeños, shishitos, and banana peppers, are bred to be harvested and eaten while green and simply won’t fully ripen to red, no matter how long you leave them on the plant.

For example, shishito peppers are usually picked when green for their best taste and texture, while some banana peppers only turn pale yellow or orange at maturity. A common question is whether all peppers can be left to turn red, but the answer depends on the specific type.

Bell peppers, for instance, are usually green when immature and turn red, yellow, or orange as they ripen, but some “green bell” varieties are selected for flavor and consistency at the green stage and rarely develop vibrant red hues. Other peppers, especially those bred for pickling or frying, may either stay green or turn a dull color rather than the bright red many expect.

If red peppers are your goal—whether for sweetness, nutritional value, or showy color—look specifically for varieties labeled as “red bell,” “ripe red jalapeño” (the chipotle pepper), or other cultivars that reliably mature to red. Read seed packets or nursery tags carefully to be sure you’re growing a type that suits your needs, and remember that patience matters: even among red varieties, full color change can take several weeks after the pepper reaches edible size.